Fentanyl is undoubtedly one of the most dangerous drugs out there. Opioid overdose is now the leading cause of death in young adults, and in 2016, fentanyl was the drug most responsible for these deaths — surpassing even heroin. In recent years, this potent opioid has begun appearing in headlines as a deeply alarming factor in America’s opioid crisis. One thing is for sure: Fentanyl is now everywhere in the U.S., and drug users are being exposed to it whether they know it or not. Even more disturbing is that the levels of exposure are almost completely unpredictable and often deadly. Understanding the history, potency and effects of fentanyl is crucial if you’re worried about abuse in yourself or someone you care about.

[maxbutton id=”2″]

What Is Fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a synthetic compound belonging to the opioid family. It’s related to medications like oxycodone and morphine, and functions the same way in the brain and body. However, depending on its formulation, fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. This fact alone is usually enough to keep people from wanting to use fentanyl recreationally, but if someone is already addicted to opioids, the high potency may appear favorable.

Similarly to morphine, fentanyl is available as an approved medication for treatment of severe pain. Fentanyl is most commonly used to control pain during and following surgery, as well as in severely injured patients. It also has uses in cases of acute, chronic pain often associated with cancer or other end-of-life care. Prescription forms of fentanyl include:

- Duragesic®: A transdermal patch

- Fentora®: A tablet placed between the gum and the cheek

- Abstral®: A sublingual tablet

- Onsolis®: A soluble film that dissolves on the inside of the cheek

- Actique®: A lozenge placed between the cheek and the gum

- Sublimaze®: An injection given by a physician usually administered by a medication pump during surgery or in ventilator-maintained patients in the ICU

The majority of prescribed fentanyl forms are patches or lozenges, meant to release appropriate amounts of the drug over time.

The History of Fentanyl

Because of how its portrayal in the news has become so widespread in the past several years, many people mistakenly assume fentanyl is a new drug. The rush to cover this growing crisis has resulted in instances of harmful misinformation circulated by the media. One common myth that has enjoyed wide circulation is that merely touching fentanyl by accident can poison you. According to the official position of the American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology, this isn’t true.

Fentanyl has been around since its development by the Janssen Company in 1960, and has become one of the most frequently used opioids in medical settings.

The emergence of fentanyl as a street drug is in response to the opioid crisis. About 21 to 29% of patients who receive an opioid medication for chronic pain misuse them, and those who end up addicted may turn to street drugs such as heroin.

Fentanyl is much more potent than heroin, and only a tiny quantity is necessary to produce the same effect. Illegal drug producers and distributors save money on transport due to the reduced weight and volume, and the savings is passed on to buyers — the higher concentration makes fentanyl more affordable. The potentially deadly trade-off is that working with very small quantities magnifies the tiniest errors in measurement and leads to wildly unpredictable effects. Typically it’s the most severely dependent who are willing to accept this trade-off or inexperienced users who do not understand the risk.

Drug dealers also use fentanyl to cut heroin, thereby saving them money. This practice leads to people unknowingly purchasing a much more potent product than they realize, often leading to overdose.

Due to these deceptive practices on the part of distributors, fentanyl is the drug most frequently involved in overdose deaths. The number of overdoses involving fentanyl jumped by 113% per year from 2013 through 2016, and fentanyl was involved in almost 29% of all overdose deaths in 2016.

Drug dealers make illegal fentanyl in illicit labs that can reach commercial scale, and the drug usually comes in powdered form. That powdered form is then cut with other substances, and inhaled nasally or dissolved for injection use. Users can also drop it on blotter paper, incorporate it into nasal sprays, put it in eye droppers or swallow it in pill form. Street names for fentanyl include:

- Apache

- China Girl

- China White

- Dance Fever

- Friend

- Goodfellas

- Jackpot

- Murder 8

- Tango and Cash

Side Effects of Using Fentanyl

Fentanyl binds to opioid receptors in the brain and throughout the body. These receptors are in areas that influence both the perception of pain centers for breathing and alertness and the way someone experiences emotions. The biological effect of this binding is a significant reduction in the body’s ability to feel pain. However, upon binding to these receptors, opioids like fentanyl also cause the brain to release a compound called dopamine. Dopamine plays a critical role in the brain’s reward pathway by triggering feelings of pleasure.

Usually, the brain only releases relatively small amounts of dopamine at a time. When you enjoy a cool glass of water or bask in the feeling of a job well done, your brain releases just a little bit of dopamine as a means of reinforcing the rewarding behaviors.

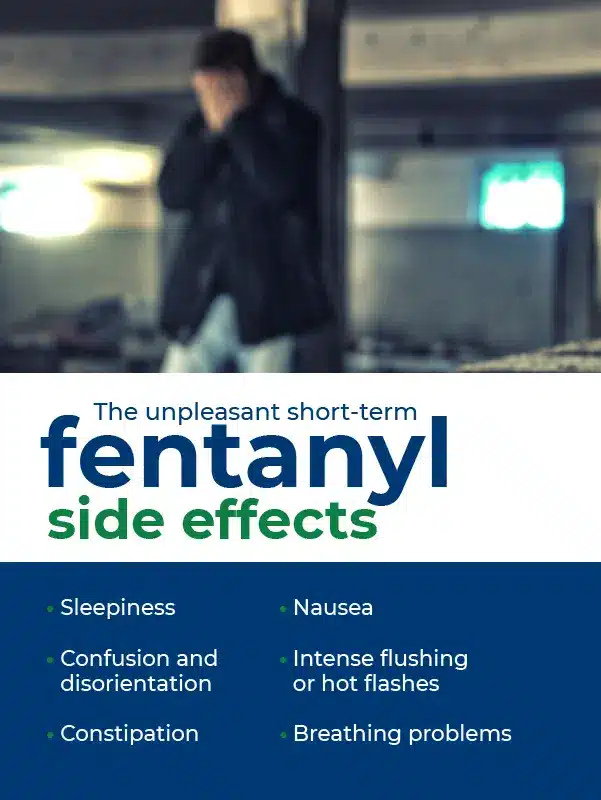

When fentanyl enters the brain and binds to opioid receptors, it triggers a massive rush of dopamine much more extensive than any ordinary activity can produce. The “high” includes feelings of extreme happiness and euphoria. Users of illicit fentanyl report it feels significantly stronger and better than heroin, but that the adverse effects come on more quickly and more intensely. Some of the unpleasant short-term fentanyl side effects include:

- Sleepiness

- Confusion and disorientation

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Intense flushing or hot flashes

- Breathing problems

Fentanyl’s short-term effects are similar to those of other opioids, but because fentanyl is so fast-acting, people who use it must inject, smoke or snort it more often than with heroin or other drugs. The extreme amount of dopamine release caused by fentanyl and misuse of other opioids also causes the brain to build tolerance, which recalibrates the amount of dopamine and pain stimulation that the body considers the “normal” state. This contributes to the onset of depression, anxiety and pain when the body does not have a constant level of opioids.

How Long Does Fentanyl Stay in Your System?

One of the medical advantages of fentanyl is that the body rapidly absorbs it, and it starts working within minutes. The system also eliminates it faster than other opioids. The most common way to use fentanyl illicitly is intravenous injection.

Fentanyl is mostly metabolized by the liver and the kidneys then remove its metabolites from urine. Fentanyl in its active form has a half-life of between four and seven hours when injected, meaning that 75% of it is removed within 14 hours. A high-quality urine test for fentanyl could detect the drug for up to nearly a week. Most tests, however, only reveal use that occurred within the last three or four days.

Blood tests can detect fentanyl for up to two days, and hair follicle tests offer the longest window of detection at up to 90 days.

Long-Term Effects of Fentanyl Abuse

One common question is, what does fentanyl do in the long run? Because opioids influence the activity of the central nervous system, they have severe effects on health over time.

One of the most dangerous long-term symptoms of fentanyl abuse is brain injury due to repeated injuries from depression of the respiratory system. These injuries can cause loss of overall brain mass, similar to what is seen in some elderly patients with dementia from accumulation of damage from many small strokes. When the brain gets starved of oxygen repeatedly, it loses function slowly. When someone stops breathing for a couple of minutes during a non-fatal overdose, the damage can be severe. The term for opioid-related brain damage is anoxic brain injury.

Long-term opioid use also has a wide-ranging pool of potential effects on other parts of the body. Studies have shown these systems can suffer damage from opioids:

- Gastrointestinal

- Musculoskeletal

- Cardiovascular

- Immune

- Endocrine

Fentanyl can interfere with every system in the body. The most insidious long-term effects are often chronic depression, pain and “anhedonia” — the inability to experience pleasure from things that would normally cause happiness. Long-term users may feel under the weather for months or years during their fentanyl abuse, not knowing the drug is what’s damaging their body. Luckily, proper treatment and sustained sobriety can at least partially reverse many of the issues associated with fentanyl abuse.

Developing Fentanyl Tolerance and Addiction

When short-term fentanyl use starts turning to long-term abuse, the first thing to look out for is physiological dependence. Drug tolerance develops as someone receives diminishing effects from the same dosage of a drug over time. Some examples are benign, such as needing two cups of coffee in the morning instead of one after several years of enjoying the drink. Tolerance does not always lead to addiction, but is one component of it.

The brain is continually trying to preserve an equilibrium of its many compounds and components. When fentanyl use triggers massive surges of dopamine over and over, the brain compensates by reducing dopamine receptors and clearing the drug from its synapses more quickly. Every time someone uses fentanyl, the brain responds to it a little less.

As fentanyl becomes a more constant presence, the brain responds less and less to natural rewards, while becoming hard-wired to operate with the drug. These brain changes drive the drug-seeking behaviors and habits that characterize addiction.

Symptoms of a Fentanyl Overdose

Because fentanyl is so potent, it’s essential to be able to recognize an overdose. If you can identify the signs of an overdose, you’ll be able to act quickly and give the person the best chance at survival and recovery. These are signs that you should call emergency services right away:

- Loss of consciousness

- Inability to respond to stimuli like lights and being touched

- Inability to speak

- Slow, shallow or erratic breathing

- Pale, bluish-purple or ashen skin

- Limp body

- Erratic, slow or missing pulse

- Vomiting

- Choking sounds or gurgling that may sound similar to snoring

If any of these symptoms appear, it’s imperative to call 911 and get emergency medical services immediately. In many states, it is legal for anyone to use the medicine naloxone to help reverse an overdose. Persons who have and know how to use naloxone (Narcan®) should follow package and prescription instructions to do so without delay. Naloxone is an opioid antagonist which prevents other opioids from working and can reverse their effects. It can quickly restore normal breathing to someone who has overdosed on fentanyl or another opioid, which is critical in preventing permanent injury or death from overdose.

The types of naloxone available to the public are EVZIO®, an auto-injection device, and NARCAN®, a nasal spray. Note that fentanyl’s potency means it may require multiple doses of naloxone to reverse the overdose. In the absence of naloxone, persons trained in CPR should assess the overdosing individual to determine if it is appropriate to begin rescue breathing or compressions while waiting for emergency services to arrive.

The Effects of Fentanyl Withdrawal

Withdrawal is the name given to the set of symptoms that occur when a dependence-forming substance is no longer present in the brain and body. To become dependent, the brain alters its normal function to respond to the constant presence of the drug. Removing it suddenly causes a series of chemical imbalances that have wide-ranging effects throughout the body. In the case of opioids like fentanyl, the earliest withdrawal symptoms include:

- Sweating and chills

- Irritability

- Restlessness

- Headaches

- Muscle cramps

As fentanyl continues to leave the system, withdrawal symptoms worsen dramatically for one to two full days. At this point, individuals can expect:

- Nausea

- Diarrhea and vomiting

- Confusion or disorientation

- Anxiety

- Insomnia

- Lack of appetite

- Shakes or tremors

- Full-body aches

These flu-like symptoms can have even the most robust person curled up and feeling like they are at death’s door. The worse the symptoms get, the more tempting it is to give in to drug cravings to get the pain to stop. That’s why getting the right treatment before withdrawal happens is key to a successful recovery.

Fentanyl is unique in that someone can go into physical withdrawal just a few hours after taking their last dose if they are taking a pure form of fentanyl. Because fentanyl, if acquired through illicit means, is usually mixed with other substances and its purity is unpredictable, there is no “typical” onset window. The beginning of physical withdrawal symptoms varies widely based on what other substance is mixed in, how pure it is and the tolerance threshold of the user.

If someone is abusing fentanyl patches, the slow release means withdrawal symptoms may take up to 24 hours to begin. Washing the skin after removing a patch will speed up the onset of symptoms.

Treating Fentanyl Addiction

People who are abusing or addicted to fentanyl are at a higher risk of overdose and permanent adverse effects than those who use any other opioid. However, people living with a fentanyl addiction can overcome it with appropriate treatment and the motivation to succeed.

Since the 1970s, the gold standard for opioid addiction treatment has been methadone maintenance. This form of medication-assisted treatment works by keeping the majority of withdrawal symptoms at bay throughout the process of recovery.

Methadone occupies the brain’s opioid receptors, but doesn’t create a high when taken at prescribed dosages. Instead, it engages the receptors enough to keep withdrawal symptoms from setting in. It is an essential step in reducing cravings to a manageable level, and allows individuals to feel relatively normal as they navigate the road to recovery.

Buprenorphine, also known as Suboxone®, is a new medication introduced in 2002, which works in a manner similar to methadone. It is also branded as Zubsolv®, and known on the illicit market as “strips” or “subs.” It is well-established to be highly effective at treating opioid use disorder, but has not been tested specifically for fentanyl use disorder. It is theorized to be likely more effective than methadone for fentanyl use disorder, but this is currently unknown.

Get a Head Start With BAART

Fentanyl addiction is a severe condition that deserves compassionate, proven treatment. BAART Programs has more than 40 years of experience providing opioid addiction treatment with a patient-focused approach. We understand the challenges and complexities of the recovery process, and we provide the tools necessary to build a strong foundation for sobriety.

BAART Programs has treatment centers located in multiple states, some of which provide medical and mental health care integrated into the programs. Every BAART location has received accreditation from the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities, and offers medication-assisted treatment programs staffed by experts.

If you or someone you love is wrestling with fentanyl abuse and addiction, BAART Programs can help. Give us a call at 800-341-4040, or reach out through our online contact form for more information on fentanyl addiction treatment.

““